How will the Charlie Hebdo attacks change France?

On Friday evening Chérif Kouachi, Saïd Kouachi and Amedy Coulibaly achieved the martyrdom they aspired to after having imposed the same fate on 17 people who had no wish to die. French leaders called for national unity after the Kouachis’ attack on Charlie Hebdo … but their legacy is likely to be fear, prejudice and restrictions on civil liberties.

Issued on: Modified:

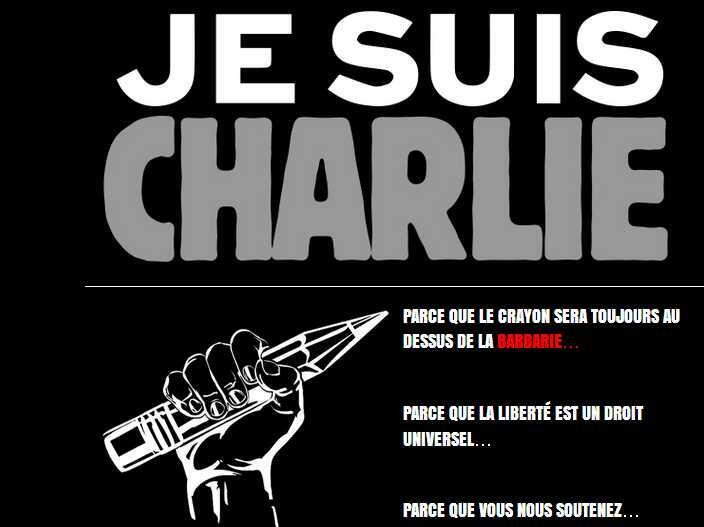

“Je suis Charlie,” was the slogan adopted by demonstrators in Paris on the day of the massacre. And it travelled round the world as politicians, journalists and members of the public declared their solidarity with the victims, killed in revenge for the satirical paper’s printing of caricatures of the prophet Mohammed.

The attack has been labelled “France’s 9/11” and it has undoubtedly traumatised the country as 2001’s attacks on New York and Washington did the US, although it is far from being France’s first experience of political or sectarian violence.

Some of the bloodiest have been a bomb in the Saint Michel metro station that killed eight and injured 117 in 1995, a Paris synagogue bombing that killed four and injured 40 in 1980 and the killing by police of an unknown number of pro-Algerian independence demonstrators in 1961.

Nor is the Charlie Hebdo attack Europe’s most deadly, as has been claimed. That distinction goes to far-right gunman Anders Behring Breivik’s slaughter of 77 people, with 171 wounded in Oslo in 2011.

But France was on edge at the end of a week that had seen the murder of journalists, police officers and bystanders, two hostage-takings and the deaths of the three principal perpetrators.

There were threats of more attacks by Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, jihadi cyberattacks on media websites, bomb scares on the metro, thousands of police on the streets and a hunt for Coulibaly’s girlfriend and suspected accomplice, Hayat Boumeddiene.

One woman from Marseille found out that the authorities were in no mood for jokes when she was arrested for shouting “I am Coulibaly’s girlfriend and I’m going to blow everything up” from the window of her hotel at the Disneyland amusement park.

President François Hollande reaction to Wednesday’s slaughter was a call for national unity in defence of “freedom of expression” and France’s “republican values”.

The following day he invited the man he defeated in 2012, Nicolas Sarkozy – now the leader of the mainstream right UMP party – to the Elysée presidential palace for the first time since that year’s presidential election.

Although he was unable to resist the temptation to lecture his successor on the need for tougher security measures, Sarkozy played the national unity game, saluting the “dignity” of the French people’s reaction and declaring that “civilised people must stand together against barbarism”.

The UMP later agreed to back the rally called at the initiative of Hollande’s Socialists for Sunday.

But that unity was soon shattered by a question that the organisers seemed not to have anticipated – should the far-right Front National (FN) be invited to take part?

Riding high on opinion polls that show her making it to the second round in the 2017 presidential election, FN leader Marine Le Pen wasted no time in expressing her indignation at not being asked to participate, claiming that declarations of national unity were a sham if her party was left out in the cold.

As she had no doubt expected, that opened up divisions in the mainstream parties’ ranks.

Former prime minister François Fillon, who, like Sarkozy, hopes to be the UMP presidential candidate in 2017, called the row “dangerous, detestable” and “what the terrorists want”.

Even if he doesn’t like the FN, he said, it is “involved in the republic and democracy” and has millions of voters who should not “stigmatised”.

The problem is that, if the FN is on home territory when it comes to denouncing “Islamist terrorism”, that is because it is generally perceived as being no friend to Muslims in general.

So left-wing and centrist politicians who do not want to see Le Pen’s party prosper, vehemently opposed according it the legitimacy of an invitation to the rally.

There is no place for a “political movement that has divided the French, stigmatised our fellow citizens according to their origin or their religion for years”, argued Socialist François Lamy.

“Madame Le Pen is trying to pass herself off as a victim … with the usual whining,” Jean-Christophe Lagarde of the centrist UDI told RFI.

The FN “advocates discrimination” and is “not a republican party”, he said.

France has the largest Muslim population in Europe and Hollande and Prime Minister Manuel Valls have taken care to distinguish between the “terrorists” and the religion of Islam.

There have already been several attacks on mosques and other Islam-related targets and the violence could deepen divisions in French society of which the rising support for the FN and the publicity given to authors Eric Zemmour and Michel Houellebecq are evidence.

Consciously or not, the attackers have done everything possible to feed Islamophobia – exercising censorship by the gun with the murder of cartoonists and, in Coulibaly’s case, fanning sectarian divisions between Jews and Muslims by taking hostages in a kosher supermarket.

They also managed to unite the majority of France’s Muslims in condemning an attack on a paper that one Islamic umbrella group took to court for alleged incitement to religious hatred a year ago.

After the first declarations of solidarity, there have been some misgivings over Charlie Hebdo’s attitude to Islam.

Some of its cartoons were judged too “incendiary” to reprint by several US media outlets.

“Even many people who were horrified by the attack have become troubled by the embrace of a paper they believe crossed the line into bigotry,” commented the New York Times’s public editor, Margaret Sullivan.

Charlie Hebdo claims to mock everyone without fear or favour – many of the politicians now defending it have been lampooned in its pages over the years - and to stand in the Voltairean tradition of anti-clericalism.

But it has grabbed headlines with its derision of what is sees as hard-line Islam, as in its republication of Danish paper Jyllands-Posten’s Mohammed cartoons and a special “Sharia Hebdo” edition, which claimed that Mohammed was its editor-in-chief.

In an article published in 2013 former Charlie Hebdo journalist Olivier Cyran claimed that an “Islamophobic neurosis gradually took over” the paper after 9/11.

“You claim to be following the anti-clerical tradition, while pretending not to know how it is fundamentally different from Islamophobia,” he wrote. “The former was established during a long, hard, bitter struggle against a Catholic clergy with fearsome power, which had – and still has – newspapers, MPs, lobbies, salons and enormous property holdings; the latter attacks members of a minority religion with no influence in the corridors of power.”

When it visited a school in the working-class Paris suburb of Saint Denis, Le Monde newspaper found the students were “not all Charlie”. They had observed the nationwide minute of silence for the victims but some found that the paper had “zero respect for us” and feared “the hatred that is still directed against Islam”.

Indeed, viewed from the banlieue, the former rebels of Charlie Hebdo look like part of the establishment, academic and journalist Andrew Hussey points out in the New York Times.

“What is seen in the centre of Paris as tweaking the nose of authority religious or political is seen out in the banlieues as the arrogance of those in power who can mock what they like, including deeply held religious beliefs, perhaps the only part of personal identity that has not been crushed or assimilated into mainstream French society,” he commented.

In fact, in France, rightly or wrongly, freedom of expression is not unlimited.

Leaving aside libel and privacy laws which politicians and celebrities occasionally make use of, holocaust denial and defence of other crimes against humanity is illegal, as is publicly insulting someone on the basis of their race or religion and incitement to racial hatred, as the comic Dieudonné found out last year when his show was banned for anti-Semitic content.

France became the only European country to ban protests against last year’s Israeli offensive against Gaza last year, the authorities citing a risk of anti-Semitic violence and public order.

Feminists of the Femen group also claim their right to protest has been denied by two convictions for “sexual exhibition” for topless stunts in a waxworks and a Paris church.

As after 9/11 in the US – and in Europe, for that matter - other freedoms may be restricted in the climate of fear that has been worsened by this week’s violence.

Council of Europe president Donald Tusk called for tougher Europe-wide security measures, including monitoring air passengers’ movements basis.

“There will be a before and an after,” Prime Minister Manuel Valls declared on Friday.

Admitting that there had been intelligence failures in monitoring the Kouachi brothers and Coulibaly, he promised “pitiless action” against “those who attack our fundamental interests” and promised an all-party consultation process on tightening up the country’s security.

Daily newsletterReceive essential international news every morning

Subscribe